George M. Cohan In America's Theater | home

Stageography | What's New | George Washington, Jr. | The Merry Malones | Broadway Jones | 45 Minutes From Broadway | About Me | The Little Millionaire | Little Nellie Kelly | The Tavern | Seven Keys To Baldpate | Ah, Wilderness! | Get Rich Quick Wallingford | The Royal Vagabond | Discography & Filmography | Early years: 1878-1900 | Broadway Rise: 1900-1909 | Broadway Emperor: 1910-1919 | Decline & Fall: 1920-1929 | Little Johnny Jones | I'd Rather Be Right | Broadway Legend: 1930-1978 | Mailbag/Contact Me | Related Links | Articles & Thoughts | The Yankee Prince

Decline & Fall: 1920-1929

At the beginning of 1920, Broadway saw the severance of it's most beloved

partnership: Cohan & Harris. Soon after "The Acquittal" opened on January 5,

George & Sam announced to the world that they would go their own separate

ways. We can only speculate as to the reasons the event occurred, because

neither one would publicly admit why. One reason must have been that Sam

Harris saw the necessity of his decision to concede to Equity and end the strike.

He must have realized when he signed the Producer's Management

Association's contract with Actor's Equity, that the producers really had no choice.

They had to give in to Equity's demands, otherwise they would run the risk of

losing talent to other producers outside their circle. Plus, each night Broadway

was dark, producers weren't putting money in the bank. One month into the

strike, he probably had pressure to end it. This created a rift with his partner.

George M. Cohan had fought a long and hard opposition against Equity,

and bitterly resented the P.M.A.'s resolution. Still, no one knows the real truth of

the situation. If the partnership's end really was due to the PMA's concession

to Equity, then why did Cohan & Harris wait almost four months before announcing

their decision? And, after it was made, why not publicly declare it? (George M.

had no reservations about publicly announcing his disposition toward Actor's

Equity)

With "The Acquittal" running strong, and a few million dollars in the bank, Cohan

once again announced his retirement. This time, it lasted eight months, and

when he came back, he opened three hits beginning in September of 1920.

In late September, "The Tavern" opened to mixed reviews, but enjoyed a long

New York run before going out on the road. By October, "The Meanest Man In

The World," a play by Augustin MacHugh, which had been Cohanized, (a story

about a lawyer who goes to a small town, and rescues a beautiful inhabitant from

her financial ruin), proved to be extremely popular with audiences. Especially

popular, when George M. stepped in to play the leading role during the run of

the show. Twenty three years later, Jack Benny starred in a film version.

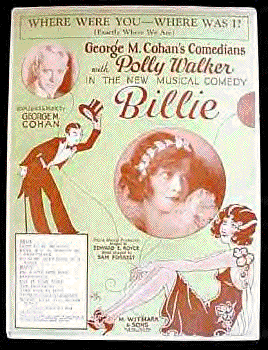

Sheet music cover of the show's

hit song.

On the heels of "The Meanest Man In The World," came a third success entitled

"Mary." Once again, Cohan had "Cohanized" another's work - this one, a

musical. "Mary" was popular with audiences all over the country, and its song

"The Love Nest" swept the nation (a small section of it appears in a

montage segment in "Yankee Doodle Dandy"). All three shows were running

concurrently, and would continue well into the next year. In 1920, it looked as

if George M. would survive the disintegration of his partnership.

However, he lost on the production of Augustus Thomas' play "The Nemisis,"

(see "Seven Keys To Baldpate" page) . This resulted in Cohan pulling further

away from arena of the dramatic field. He decided to play it safe and produce

another musical from the team who wrote "Mary" called "The O'Brien Girl." It

too proved popular, but the playwriting formula used was beginning to become

apparent to critics (they complained the plot line was dated even in 1921).

In January 1922, George M. was unanimously reelected and returned to The

Producer's Management Association. He accepted and continued his

attack on Actor's Equity (see Articles & Thoughts section ). Years afterward,

he confided to a friend, "about that strike - if one actor, just one actor, had ever

called me up and said, 'Georgie, we're going to pull that show of yours at the

Cohan, but we don't mean you,' it would have made one hell of a lot of difference."

By 1922, Georgette Cohan (his first daughter) was twenty-one, an accomplished

pianist, and she had expressed to her father an interest in performing. George

quickly wrote a comedy for her to star in entitled, "Madeline & The Movies." The

story line was about a beautiful young girl while getting help from an established

movie star, becomes terrified her father and brother will misunderstand their

relationship, and do harm to the older actor. During the run of the show, when

the show's financial failure was becoming obvious, Cohan stepped in as the role

of the father to boost the "gate." This worked for a short time but the inevitable

soon gave way. The production didn't prove helpful or worthy to either Cohan.

Georgette would soon marry and leave the theater.

Cohan opened the 1922 season with "So This Is London" which proved to be

one of his longest running productions. Written by Arthur Goodrich, and starring

Lilly Cahill with Edmund Breese, Cohan reworked most of the dialogue but

refused a writing credit. His rule was that if he had written at least 50% of

the play, then, and only then, would he accept a writing credit. The play was

reworked and made into a movie in 1930

Later that year, George M. returned to the world of musical comedy with his

successful, "Little Nellie Kelly," followed by "The Rise Of Rosie O'Reilly" in

1923. Again Cohan provided a memorable score with such songs as "Let's

You & I Just Say Goodbye," "Love Dreams," and the irresistible "Ring To The

Name Of Rosie," which was later performed in "George M!" "Rosie O'Reilly"

starred Jack McGowan (later a Hollywood screenwriter and Broadway

director), as a millionaire, who was in love with a young Irish beauty, who sold

flowers at the base of the Brooklyn bridge.

The formula Cohan used for his musical successes in the early 20's was beginning

to show. "The Rise Of Rose O'Rielly" was only a moderate success and audiences

had become enchanted with a new form of music, one that George M. didn't

write: jazz. Additionally, America had changed its taste in entertainment. The

Roaring 20's were now getting into full swing, and George M. Cohan found himself

in a position he hadn't been in since the days of his struggles in vaudeville; he was

becoming unpopular.

One play he wrote in 1923 that did prove to be favorable with the critics

was "The Song & Dance Man." The plot of the "The Song & Dance Man"

concerns a song and dance performer who could never escape his love of the

theater. As Hap Farrell, Cohan portrayed a penniless vaudeville song & dance

man, who after earning financial success as a miner, decides he'd rather go back

to performing, even with its financial uncertainty. The play was basically Cohan's

daydream at the question - what if he and his family never left vaudeville? What

would have happened to them? In his autobiography, "Twenty Years On

Broadway, And What It Took It Get There," Cohan responded to the critical

acclaim of his acting.

Cohan is the

"Song & Dance Man"

"And now comes the big laugh of the story, the real punch to the tale. The

actors admitted that I was a good actor. Gosh darn it! Why did they keep me

waiting so long? Well, anyway, at last I'd come into my own. My dreams had

all come true. My highest ambition satisfied at last. Hurrah! I'm a good

actor!"

The next year, George M. again tried something different. He decided to write his

memoirs down and called it, "Twenty Years On Broadway, And What It Took To Get

There." In it, Cohan looks back at the early struggles he endured as part of The

Four Cohans in vaudeville. He dedicates very little space to his career after

1900, and has little or no mention of his own family, Ethel, the Equity strike, or

the breakup of his partnership with Sam.

By 1925, the national change of America's entertainment taste (that had been

brewing for the last few years) came into fruition. Jazz was now the popular

music, and composers like George Gershwin (whose brilliant "Rhapsody In Blue"

was released the year before), Irving Berlin, Jerome Kern, and the team of

DeSylva, Brown, & Henderson, were now composing for the top Broadway

musicals. Eugene O'Neill had become the top playwright in American, possibly

the world. Performers like Al Jolson, Eddie Cantor, Fred & Adele Astaire, Marilyn

Miller, Lunt and Fontanne, were dominating the hearts and minds of playgoers.

George M. Cohan played no part of this movement. He works belonged to the

world of the previous two decades. The failure of "American Born" (1925)

couldn't even be saved by George M. starring in it himself. "The Hometowners"

(1926) despite having been made into a subsequent film two years later, was

also a disaster.

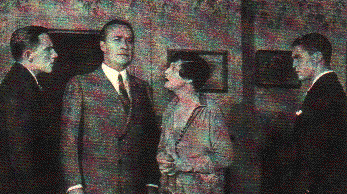

Cohan in

"American Born"

That same year Cohan also produced and directed a play "Yellow" which debuted

an actor that he truly admired. A young, 26 year old named Spencer Tracy.

By the same token, Tracy had so admired Cohan, that he developed stage fright

just knowing that Cohan was watching him in the empty theater. Cohan believed

in the young actor, and asked to be introduced to him (he later publicly called him

"the best Goddamned actor I ever saw"). The two soon formed a friendship that

lasted the rest of Cohan's life. Tracy later is quoted when he recalled that first

time he met Cohan. "Do you know what you did for me then, George M.? You

gave me faith in myself. Just as you've given it to hundreds of others. Somehow,

through just a word or a gesture, you convey to a person that you believe in

them - and so they believe in themselves." The only acting advice Cohan gave

to Tracy was simple in concept, but one that a lot of actors of the 20's had yet

to master. It was a style that Tracy not only mastered, but catapulted him to the

status of superstardom. Cohan advised him, "Spencer, you have to act less."

Cohan's only disappointment in his relationship with Spencer Tracy, was when

he left the artistically rewarding Broadway theater for the less serious, but

financially rewarding career of making films in Hollywood.

Spencer Tracy (far left) and Hale Hamilton in a

scene from "Yellow" (1926)

Cohan and Spencer Tracy worked together once more the following year. In

1927, the comedy, "The Baby Cyclone" opened to the delight of audiences.

The show was a minor hit about a Pekinese dog (Cyclone), who is favored by

his mistress, and gets sold by her husband (Grant Mitchell) who can't stand the

dog, or the way his wife treats it. During the course of the story he realizes that

the guilt he suffers from his wife is far greater than when Cyclone was there.

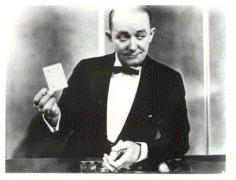

Grant Mitchell in "The Baby Cyclone" (1927)

Two weeks later, Cohan found himself starring in "The Merry Malones."

Cohan's personal life was full of surprises too. His eldest daughter, Mary, had

eloped with a banjo player named, Neil Litt. The elopement caused George

M. emotional pain, and was a reminder of just how distant he was from his

own family.

In late summer of 1928, Nellie Cohan passed away at her home in Monroe, New

York. George was now the only one left of the Four Cohans. The death of his

mother caused him considerable grief. It seemed the only way he could get past

any of his troubles was through his work.

In 1928, Cohan also found another actor who's style he found refreshing;

Walter Huston. Huston had already appeared on the Broadway stage for four

years (he appeared in the original cast of Eugene O'Neill's "Desire Under The

Elms"). After a hard night of drinking Cohan & Huston agreed that he would

appear in a new play Cohan was producing. A baseball play entitled, "Elmer

The Great." During rehearsals, Cohan helped Huston understand the value of

underplaying a role. This technique Huston absorbed and - like Spencer

Tracy - was something he brought to his long and brilliant film career. Cohan

was very pleased when Walter Huston was cast to play his father, Jerry in

"Yankee Doodle Dandy." Huston always remained one of Cohan's favorite

actors.

After producing "Elmer The Great," George M. took the last show that his

parents appeared in, (Broadway Jones) and rewrote it as a musical. Polly

Walker, (who also starred in the "Merry Malones") appeared once again as

Billie, and it's title song, is and irresistible beauty.

Sheet music cover from "Billie"

"Billie" was the last musical George M. Cohan wrote. The critics complained

the usual (it was too old fashioned), and George M., (disappointed that he had

to close a show whose form he had mastered so long ago) decided to give his

musicals a rest. He was very disappointed with a world where he was once the

renown king, but now one that he didn't understand at all, and didn't understand

him.

After his mother's death, he sold his home in Great Neck, Long Island and

moved his family to his parents home in Monroe, NY.

Cohan's last performance during the 1920's was in the show, "Gambling." Five

years later, it was made into Cohan's second talking film. In the play, Cohan

plays a gambler, who sets out to expose the murderer of his adopted daughter.

On the road, another unknown actor portrayed the daughter's boyfriend and killer,

Clark Gable. It opened in August of 1929, and lasted well into the following

year after the stock market crash.

A still from the film version of

"Gambling" 1934