George M. Cohan In America's Theater | home

Stageography | What's New | George Washington, Jr. | The Merry Malones | Broadway Jones | 45 Minutes From Broadway | About Me | The Little Millionaire | Little Nellie Kelly | The Tavern | Seven Keys To Baldpate | Ah, Wilderness! | Get Rich Quick Wallingford | The Royal Vagabond | Discography & Filmography | Early years: 1878-1900 | Broadway Rise: 1900-1909 | Broadway Emperor: 1910-1919 | Decline & Fall: 1920-1929 | Little Johnny Jones | I'd Rather Be Right | Broadway Legend: 1930-1978 | Mailbag/Contact Me | Related Links | Articles & Thoughts | The Yankee Prince

Broadway Legend: 1930-1978

As 1930 began, George M. Cohan's career seemed to be over. He tried to jump-

start it by reviving "The Tavern" & "The Song & Dance Man" for a brief run on

Broadway and subsequent tour, which proved to have some success. When he

returned to Broadway, his first play of the new decade, Friendship (1931), costarred

himself with his daughter, Helen. It lasted only 3 weeks on Broadway. Richard

Lockridge, critic for the New York Sun, summed up Cohan's play writing problems

(of recent years) in his review of "Friendship:"

"Mr. Cohan is infinitely more ingratiating as an actor than as a playwright...His

unabashed special pleading, his refusal to permit his antagonists even the most

obvious of rejoinders, his discrimination to portray one grain of good sense in

any character under fifty - these things help neither his argument nor his play."

By 1931, George M. moved into an apartment at 993 5th Ave. It was at this

address that he used to meet with theater critic, Ward Morehouse who would

later write his biography, and where he would spend his final days.

In need of a vehicle to give some vitality to his fledging career, Cohan agreed to

a proposition by an old friend, Jesse Lasky (a high ranking executive at

Paramount) and appear in a musical film. With contract signed, Cohan left for

Hollywood, ready to work the minute he set foot in California. When he arrived,

he was told that the production was postponed due to an internal upheaval

within the front office. When the dust at Paramount had finally settled, Jesse

Lasky was gone, and George M. Cohan was at the mercy of studio executives

that had no idea of what to do with him.

"The Phantom President" was a dismal event in the life of George M. Cohan. It

proved to him that film making was not something he wanted to pursue. Richard

Rodgers and Lorenz Hart were brought in to score the music, and it was far from

their best work (possibly even their worst). Claudette Colbert was wasted in a

role that had no depth at all, Sidney Toler (famous for his Charlie Chan roles)

added a spark of humor that really went no where. Jimmy Durante was, well

JImmy Durante, and George M. Cohan played a duel role. One, was that of a

presidential hopeful with an especially dull personality, and the other was his

alter ego, a medicine show man named, Dr. Varney.

"The Phantom President" (1932)

with Claudette Colbert

There were two highlights in the movie. 1) A quick entrance by Cohan where he

greets his presidential double with a dance routine, and 2) when he performed

"Maybe Someone Ought To Wave The Flag." However, even when they had

Cohan in front of the camera doing his song and dance routine, the director

(or one of the executives) made the decision to put him in blackface. Perhaps

the film was heavily edited down from its original script (it has that feeling

about it).

The good news about "The Phantom President" is that we get a glimpse of Cohan

performing a song and dance routine. The bad news is that the song itself is a

disappointment, and that Cohan appears in blackface (something he was never

known for, and in all his appearances in the legitimate theater didn't do). "The

Phantom President" might have had potential, with the right script and music,

but now all that remains is a botched job.

When Cohan returned to New York, he commented on the experience to Ward

Morehouse his feelings about the film industry.

"Those fellows didn't know anything about me. Lot of them had never heard of

me and didn't care to be told. They treated me like a man from another world.

On the level, kid, Hollywood to me represents the most amazing exhibition of

incompetence and ego that you can find anywhere in the civilized world. From

all I could make out the only people with any sense are the technical boys and

the camera men. Those camera men saved my life. When I left I thanked them

for a million laughs. I didn't say goodbye to any of the executives. Couldn't find

them. They were away on weekends..."

Back on Broadway, George M. tried to forget his Hollywood experience. He

created new lyrics to his song "Over There" in honor of the Democratic

Presidential Candidate for 1932, Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

Cohan publicity photo (circa 1933)

A month or so later, he developed an idea he had called "Pigeons & People."

He knew he'd have to star himself in the play (in order to maximize the box office

receipts) but that didn't bother him. What bothered him was that he was now

being hailed as one of the finest actors in America yet, none of his shows in the

last few years, had gotten good reviews. "Pigeons and People" was a one act

play (something Cohan dreamed up as a gimmick) that lasted until 10:30. The

leading character, Parker (played by Cohan), is very reminiscent of the

Vagabond in "The Tavern."

As Parker in

"Pigeons & People"

"Pigeons and People" didn't achieve what Cohan was hoping for, but shorty

afterwards he was made an offer he couldn't refuse, and didn't: "Ah Wilderness."

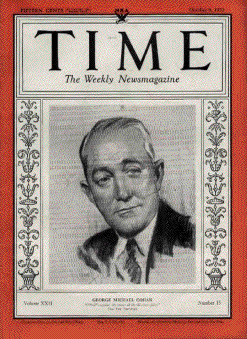

Cohan on the cover of Time - 1933

With the success of Ah, Wilderness! Cohan was back on top. Not in the way

he was accustomed to, (he had only starred in the play) but back on top

nonetheless. In 1935, he was asked by the Players Club to revive his most

popular, and enduring show, "Seven Keys To Baldpate." Cohan happily

accepted.

His next show, "Dear Old Darling" opened on March 2, 1936. Critics again sang

the praises for Cohan's acting, but condemnation of his play, and the theater -

goers seemed to care for neither one. The first week's box office yielded only

$8,000. Cohan advised his staff, "If they don't like it, we'll take it off," which

he did. The show lasted only two weeks which caused considerable frustration

and depression for Cohan.

Soon afterward, his daughter Mary divorced Neil Litt, and returned to the

Cohan household in Monroe, NY.

Amid the dismal times after "Dear Old Darling," Cohan received notice from

Congress that he had been awarded a Gold Medal of Honor, for his writing

of 'You're A Grand Old Flag," and "Over There." This medal, awarded to

Cohan on June 29, is not to be confused with the Congressional Medal

of Honor which is awarded to soldiers for personal valor, but rather a

Congressional Medal of Honor for specified services. This was the first time

that Congress had awarded a medal for songwriting, and it puts into

perspective just how powerful and how inspirational Cohan's songs were to

America. All Cohan had to do was to pick up the award from FDR. By 1936

however, that sounded easier than it was. Cohan had come to loathe the

President four years after he dedicated "What A Man" to him. The Medal would

stay with Roosevelt for another four years. (Cohan probably figured that FDR

might not be reelected for a third term - in reality, if he waited much longer, he

wouldn't have received it at all)

After the show, or on any given evening, friends and admirers could discover

Cohan sitting in a corner of Trader Vic's Bar at the Plaza Hotel (59th Street

& Central Park West). There, he would tell his stories of the theater of forty or

fifty years ago, and comment on his confusion over the contemporary theater.

It is also the final resting place of his Congressional Gold Medal of Honor.

In the spring of 1936 George M. set out to discover land of his ancestry.

A friend recalled that the aged song & dance man was wide-eyed, and excited

to see the Emerald Isle. When he returned in time for his birthday, he celebrated

it with his family and Sam Harris. Sam had found an opportunity for the two of

them to work together once again. It was a script by a radio comedian named

Parker Fennelly called "Fulton Of Oak Falls." All parties realized that the script

needed a great deal of "Cohanizing" - which it got.

Playbill for "Fulton Of Oak Falls"

Broadway was all a buzz about the reunion of Cohan & Harris. However, the

union lasted for only 37 performances. "Fulton Of Oak Falls" was yet another

disappointment. In 1937 George M. set sail once again for Europe. He had

an idea of trying his hand at the London stage. Agnes set sail with him, and

the two were enjoying Europe when Cohan got a sudden call from Sam Harris

to return to New York. Sam had a part for him in his new production that no other

actor could do. The role was Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and the play was "I'd

With the success of "I'd Rather Be Right" Cohan found himself apart of many

different social functions and dinners. One of these "The Catholic Actor's Guild

Dinner" was recorded and Cohan's acceptance speech can still be heard. He

begins by stating that the ceremony "is as much a tribute to my father, than

anything else." Jerry J. Cohan was one of the founding member of The Catholic

Actor's Guild.

With the success of "I'd Rather Be Right"

George M. Cohan continued to be an icon

of his profession.

After touring the country with "I'd Rather Be Right" Cohan brought Agnes (who's

health had been declining) to their home in Monroe, NY.

There was some talk that had been circulating about a play being written,

based on George M.'s life's story. Later in 1939, "Yankee Doodle Boy" by Walter

Kerr (theater critic and playwright), debuted at the Catholic University's Harlequin

Club in Washington DC . The program (under direct consultation of George M.)

had very little to do with the facts of his life, and was basically a revue for his

music. Only a month earlier, in November 1939, Cohan had opened a show

entitled, "Madam, Will You Walk?" written by Sidney Howard, and produced by

Robert Sherwood. Sherwood insisted that the role he had Cohan in mind for

was a lot like the Vagabond of "The Tavern." That intrigued Cohan. Sherwood

also assured him that he felt no other actor on the stage could do it. But, Cohan

didn't feel completely comfortable cast in the role of a suave Lucifer, and in

Baltimore, after a few performances, the theater critics agreed. It was enough for

Cohan to quit the show and return to New York.

On March 6, 1940, Mary Cohan eloped for a second time. This time to an accordian

player named, George Ronkin. The act of the elopment hurt him deeply.

Later in the spring of 1940, Cohan put aside his feelings about President Roosevelt,

and made the journey to the White House, where he was presented with his

Gold Medal Of Honor.

George M. Cohan had become tired of appearing in plays written by others and

the following year, saw his last performance/writing efforts on a Broadway

stage. "The Return Of The Vagabond" (1940) was Cohan's sequel to his favorite

play "The Tavern." In it, a young performer named Celeste Holm got her first

Broadway break. However, it soon proved to be a dismal failure, and

the show lasted only one week. At the close of the final performance, George M.

confided to Celeste Holm, "I'll never come to New York again. They don't want me

any more."

Sheet Music Cover

From the 1934 Film

"Gambling"

Even as the truth of his professional career daunted him, George M. couldn't

quit the business that had been a part of him all his life. At the close of 1940,

he began developing an idea for a musical comedy entitled, "The Musical

Comedy Man," with a lead/title character that closely resembled himself.

In July of the following year, his long-time partner, and best friend, Sam Harris

died as a result of intestinal cancer. Shortly after, George M. was also

diagnosed with the same illness. In mid-October of 1941, Cohan suffered

severe abdominal pain. He was quickly taken to the hospital for an emergency

operation that saved his life. He moved in with Agnes and the children to "get

some rest and catch some sunlight."

Earlier that summer, Cohan secured a deal with Warner Brothers to tell his life

story on the screen. It now became his main goal. Writer, Robert Buckner had

the task of satisfying Cohan's desires of the content of the script. It was to have

certain boundaries which were not to be crossed. Cohan didn't want very much

of his personal life portrayed in the movie (much like Kerr's "Yankee Doodle Boy").

There would be no mention of Ethel Levey, or the 1919 Actor's Equity Strike.

Likewise, none of his children were mentioned, and the love interest that was

supposed to represent Agnes, was given the name Mary. Back and forth Buckner

and Cohan went as they hammered out draft after draft. Warner Bros. meanwhile,

had the foresight of casting James Cagney as Cohan. Cagney was a performer

whose kinetic energy and dynamics matched Cohan's and his acronym of

success on the stage ("Speed, speed, and lots of it"). Cagney had only seen

George M. perform in "Ah, Wilderness!," so he studied very closely Cohan's

dancing in "The Phantom President" (where you see Cohan doing a few of the

steps later duplicated by Cagney). Cagney also worked very closely with

choreographer, Johnny Boyle, who was in the chorus of "Cohan's Revue of 1916."

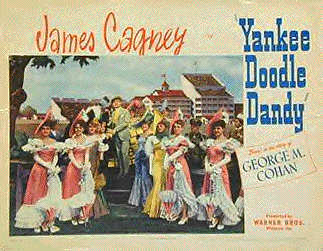

James Cagney sings "The Yankee Doodle Boy"

However, much of the dancing is Cagney's own style. His dancing in the "Give

My Regards To Broadway" sequence was unique to Cohan, while the performance

of "Off The Record" was very similar to George M.'s style. Likewise, the set

design for many of the musical sequences depicts so perfectly the original

(i.e. see flyer from "I'd Rather Be Right").

Shooting began during the final months of 1941 and beginning of 1942, and

soon a rough cut was sent to the ailing Cohan in Monroe, NY for his approval.

Cohan sat there and watched silently. After the film had come to a close, the

lights went up, Cohan shook his head in acceptance and said, "My God, what an

act to follow."

James Cagney was brilliant in the role. He portrayed Cohan without imitating him,

and won an Academy Award for Best Actor.

Original Lobby Card from the film

As "Yankee Doodle Dandy" was preparing for release, Cohan's health continued

to decline. On January 2, Cohan had a second abdominal operation - the

cancer had spread. Now, he knew he hadn't much time left, and wanted to visit

New York once again. On his return to 993 Fifth Ave., Cohan confided to close

friends that his end was near, but he kept the severity of his illness from his family.

Throughout his illness he worked on "The Musical Comedy Man."

In late summer of 1942, and against the better judgment of his nurse, Cohan got

into a cab, and took a final look at his beloved city. The cab drove down to Union

Square, where the Four Cohans first New York appearance took place. Then,

back uptown to 43rd Street where the Cohan Theater had once stood, and then

up and down the various streets of the Broadway district to see his memories

once again. The final stop was at the Hollywood Theater where he caught a few

minutes of "Yankee Doodle Dandy."

For the rest of that summer and fall George M. Cohan was quite ill. He became

confined to his apartment at 993 Fifth Ave. During this time, he was visited by

his children, and each made amends with their father. The end came on

November 5, 1942. Shortly before, his close friend Gene Buck had reminded

him of his accomplishments. Cohan grinned and added, "No complaints kid, no

complaints." He was read his last rites by Monsignor John J. Casy, and Father

Francis X. Shea. Then, just before he slipped into a coma he asked Buck to

"Look after Agnes." They were his last words.

At his funeral in St. Patrick's Cathedral, the organ played "Over There" softly to

its attendees. His body was then taken to the family plot at Woodlawn Cemetery

in the Bronx, and there he joined the other three Cohans.

The following year, theater critic and friend Ward Morehouse's biography of Cohan,

"George M. Cohan, Prince Of The American Theater," was published.

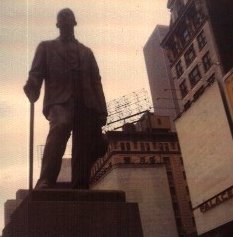

Fifteen years later, a statue of George M. Cohan was erected at 46th Street in

Times Square. Oscar Hammerstein II (long time songwriting partner of Richard

Rodgers) led the committee to bring the event about. In an article in the New York

Times commemorating the unveiling of the statue, Hammerstein wrote:

Cohan's statue in Times Square

"Never was a plant more indigenous to a particular part of the earth than was

George M. Cohan to the United States of his day. The whole nation was confident

of its superiority, its moral virtue, its happy isolation from the intrigues of the old

country, from which our fathers and grand fathers had migrated."

The $58,000 fund was made from various contributions of prominent people in

the theater.

It seemed that George M. Cohan's story was still as popular as ever in the late

50's and early 60's. All together, three different versions of his life (two on television,

one on the Broadway stage) were made. The best of which was Broadway's

"George M!" with the charismatic Joel Grey (fresh from Cabaret) and a young girl

who would remain in the theater for many years, Bernadette Peters. Mary Cohan

was brought on to make some lyric and musical revisions (example: the song

"My Town" in "George M!" was originally "I'm A One Man Girl" from Cohan's

"Billie"). "George M!" gives the best example of Cohan's musical compositions.

All together, over twenty-five different songs are performed, and the variety of

music is even better than "Yankee Doodle Dandy's."

During the early 1970's The American Guild Of Variety Artists began televising

an annual award ceremony. Their award was a statue of George M. Cohan, and

the award was called the "Georgie."

In 1973 John McCabe's book "George M. Cohan - The Man Who Owned

Broadway" was published. McCabe has gathered many first hand accounts of

Cohan that have since vanished from our midst. It is to date, the best biography

on Cohan.

By 1978 Cohan's popularity was well over. Yet, on the centennial celebration of

his birth, the US Post Office released a stamp in his honor. This was one of the

first of many stamps to honor members of America's performing arts.

The family of George M. Cohan is equally as elusive as many facts in George M.

Cohan's private life. Agnes Cohan lived to the age of 89. She always would sing

along whenever "Yankee Doodle Dandy" came on television during the 1960's.

She passed away on September 9, 1972.

Georgette, Mary, Helen, and George Jr. virtually disappeared (with the exception

of Mary's work for "George M!"). During the 1950's George Jr. re-recorded a few

of his father's songs but nothing else was ever heard of him. Helen is reported

to have passed away on Sept. 14, 1996. But, no other information is available on

any of George M. Cohan's off-spring.

George M. Cohan's private life remains private. He guarded it well, and as the

years roll on, his personal matters drift further away. As for his work, some of it

still survives, his music is still heard, his name occasionally, and the play "George

M!" still is alive in regional theater. And, television occasionally plays "Yankee

Doodle Dandy" - it's subsequent Home Video releases (for almost 20 years)

has never gone out of print. But unfortunately, neither one was able to capture

Cohan's real story.

"And so he snuck off, all alone and by himself, and noboby didn't see him

no more."

- Peck's Bad Boy