George M. Cohan In America's Theater | home

Stageography | What's New | George Washington, Jr. | The Merry Malones | Broadway Jones | 45 Minutes From Broadway | About Me | The Little Millionaire | Little Nellie Kelly | The Tavern | Seven Keys To Baldpate | Ah, Wilderness! | Get Rich Quick Wallingford | The Royal Vagabond | Discography & Filmography | Early years: 1878-1900 | Broadway Rise: 1900-1909 | Broadway Emperor: 1910-1919 | Decline & Fall: 1920-1929 | Little Johnny Jones | I'd Rather Be Right | Broadway Legend: 1930-1978 | Mailbag/Contact Me | Related Links | Articles & Thoughts | The Yankee Prince

Articles & Thoughts

The following excerpts are from an interview with Cohan, in which he discusses

the origins of his unique dancing style.

"The Practical Side Of Dancing"

"I really think I had an awful lot to do with bringing in the eccentric dance because

I was the first who tried to get way from the "standing still" dance. I had been

doing it out in the woods for years before I ever came to the big cities. When I

first played New York at the Union Square for Keith (B.F. Keith, half of a monopoly

on all vaudeville), my dancing was a revelation as they had seen nothing like it,

but inside of a season they were all doing my dancing. "They all went for it." It

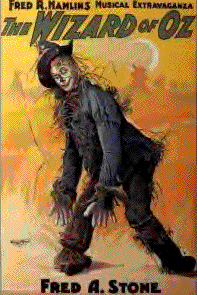

really was the beginning of the eccentric dance of today. Along came this

fellow Stone (Fred Stone, who was the original Scarecrow in "The Wizard Of

Oz" 1903) a few years later with his really marvelous dances. Of course

when he started to do his stuff he just set the people crazy.

--------------------------------------

Well, as I said I didn't dance at all until I was ten or twelve years old. Didn't

know whether I could act, but when I went into an act where I needed it it

came very naturally to me. I went after it and discovered I was a pretty good

dancer and didn't think of anything else for a couple of years until I had a

good chance to size up the situation. I made up my mind that if I was going

to be an eccentric dancer I would have to give up all my time to it and get

a new kind of a dance, so I began to do eccentric things, crazy things, such

as throwing my head back, jumping from one part of the stage to another,

etc. Yes, I originated what is called the "lazy dance."

---------------------------------------

I continued along these lines but I made up my mind that the only way to

become a big dancer was to get out of the beaten path and do something

different. After that I always tried to be a little bit different.

----------------------------------------

By the time they called me the best dancer in America I had forgotten all the

dancing I knew practically. As far as dancing itself is concerned I have not

really forgotten it, but I have practically done away with it, but at the time I

was a crackerjack dancer they were paying no attention to me at all; I was

just one in a thousand.

------------------------------------------

My father was a great dancer. He was also a writer. Wrote a lot of

melodramas, comedies, farces, etc. he experienced the same thing -

always called him a song and dance man and nothing else. I would not

play without him. My father is very fond of the stage. He began very

young. He was with a minstrel when he was about 15 years old. He was

a dancer as a kid but went away to war as a doctor's orderly. Was in two

or three battles and lost a thumb in the war - shot it off himself celebrating

a victory. "

-------------------------------------------

In an article about his own dance style origins, Gene Kelly gives some insight

into the influences Cohan had upon the Hollywood musical, as well as, acting

styles.

In "An American In Paris" Kelly

uses Cohan's style of dancing to

illustrate the "typical" American

In Paris.

"Cohan set the stage for the American song-and-dance man - a tough,

cheeky, Irish style. Cohan wasn't a great dancer, but he had wonderful

timing and a winning personality. He influenced a whole breed of actors,

including Cagney, Spencer Tracy, & Pat O'Brien - and when Cagney did

Cohan in "Yankee Doodle Dandy" he was an improvement on the

original. Cohan was the American Theater up until the impact of Eugene

O'Neill, and I have a lot of Cohan in me. It's an Irish quality, a jaw jutting,

up on the toes cockiness - which is a good quality for a male dancer

to have, and it's a legacy from George M. Cohan."

Saturday Evening Post - September 3, 1910

Cohan wrote a lengthy article for this edition of "The Saturday Evening

Post." It is a reminder that while styles have changed, the basic emotions

and insecurities of the artist are still the same. Here are a few excerpts:

"The Actor As A Business Man"

"But why does a manager say that the actor is the best business man in the

country? In the first place, he is a shrewd advertiser. He knows the value of

personal fame to the dollar and avails himself of everything that adds up to

his reputation. Even outside agents are not despised. His methods are

progressive. Near-automobile accidents succeeded diamonds and divorces,

which used to be good mediums of notoriety. Probably daring aviation

or something quite as sensational will come next. The illustrated interview

with the actor in the Sunday section counts for little today. The public is too

used to his stilted style of off-stage talk - his cynicism - his roasting of

audiences and the like.

A few years ago the actor got so little that he never could save enough for

large investments. To put his money in the savings bank of any particular

city left it unavailable for sudden demand when on the road - a contingency

not wholly unknown to actors. To carry a big roll was a temptation to himself

and to all predatory persons who should chance to see it. Nowadays, the

actor invests his money mostly in real estate. He is great for first mortgages

on city property. It has become a hobby with him to buy a small farm

somewhere and tuck it away, so to speak, as a last resort; for he has a

keen sense of the exigencies of his business....

A traditional superstition with the actor is that the manager is always trying

to get the better of him. So he is always on his guard. When he gets

through blue-penciling a contract which the manager submits it is so

skillfully changed that it's the actor's proposition, and not the manager's,

which is signed. Thus, with consummate adroitness, he secures for

himself every advantage that the manger thought he was getting. The

most astonishing sample of this kind of work was pulled off by the late

Ezra Kendall. That gentleman took the manager's contract, cut out the

middle, leaving only the heading and the border, pasted his own

proposition in the frame, sent it back, and the manager signed it."

---------------------------------

"Harry Lauder makes five thousand dollars a week for the 20 week

engagement he plays in America. Besides, he gets 500 dollars for

singing one of his songs into the phonograph. His five month American

tours yield him one hundred thousand dollars. Then he goes home and

plays. He is booked to do this for two years. What manager is in the

Lauder class as a moneymaker?

If Maude Adams should leave Frohman there isn't a manager in the country

who wouldn't guarantee her five thousand dollars a week. Recently, she

took in twenty four thousand dollars in one week with her small,

comparatively inexpensive company, in "What Every Woman Knows." Are

you beginning to see the reason for the manager's change in attitude?"

---------------------------------

"With the manager, the play business is speculative from beginning to end.

The speculation begins with the reading of the submitted manuscript. No

one ever lived who could more than guess the effect of a play on an

audience. The reading of it is no criterion. It must be tried out in public.

One may not think a certain line funny while reading a play or seeing it

rehearsed, but he would begin to laugh with the public who should see

fun in that line. This is the psychology of the crowd - the most subtle

element a manager has to deal with."

------------------------------------

"It costs from ten thousand to thirty thousand dollars to produce a modern four-

act play. This, over and above fixed charges, must be paid back before the

manager begins to see daylight. Nor do the gross receipts go into his pocket

alone. The house he plays receives from thirty to fifty percent.

There has never been any "important money" made by producers who are in it

solely for the cash. If it's a cold-blooded money making proposition, the owner

will go broke. One must like the work for itself alone - must be enthusiastic,

imaginative, eager. The only way to do is to get in on the theater end of the

proposition if one would stand a chance to "break even." If he has a house

(theater) and has a good show, he will be sure to make money. Everybody

now realizes that there is no money in musical productions. The expense

of bringing these out is appalling, and a small fortune may be sunk in

maintaining a show while it is being tried out.

--------------------------------------

I have often wondered what the result would be if a party of actors were left

to themselves to put on a play. It would be like a lot of small boys trying to

sail a ship. They'd all want to be commanding or steering, or running up and

down the rigging, or doing other spectacular stunts that to the spectator would

be about as coherent and comprehensible as the romping of a lot of monkeys.

And if one were chidden he'd do the regular simian sulking act.

In this respect the actor always seems to be under the delusion that he is being

discriminated against, held back either for spite or some other mysterious

purpose that the manager may have up his sleeve - just as if it weren't to the

manager's interest to push the actor ahead!

"Why don't you give me a part I can sympathize with?" says the actor.

"If I did it would be impossible for any one else to act in the play with you."

"Why?"

"Because there'd be only one part to it," and the manager closes his roll-top

desk with a bang.

The actor watches him for a moment, then says: "There he goes - to the ball

game, and I've got to play a matinee."

In an open, and undated letter Cohan explains his position on Actor's

Equity. This article is a fascinating, first hand look into a subject that

Cohan generally remained silent about.

"To The Members Of The Acting Profession"

Don't let them tell you the Equity shop is not a "closed shop." Don't let them

trick you into something down deep in your hearts, you know you don't want -

to crush out all opposition. To force every member of the acting profession

into one organization, to be compelled to place your affairs in the hands of

a few self chosen leaders, and to be ruled by, and dictated to, and to just how

and when, and where you are to act, and to be placed in the position that

unless you work and live according to the rules and regulations laid down

by a few "radicals," you will find yourself without any place to turn - without

any alternative but to pay any penalty they care to place upon your head

in the severest form of closed shop.

And, that is exactly, what they are edging you up to by trying to make you

believe that it is something it is not - they can call it "Equity shop" or any

other old shop at all, but its "closed shop" just the same and it spells ruin to

the acting profession - I am not speaking for any organization of managers.

I am not a member of the P.M.A. (Producers Management Association). I

withdrew from that body during the strike when I became a member of "The

Fidelity League." There is one more thing I fought for throughout the strike,

and only one thing, and that was for "open shop." There is one thing I will

fight for as long as I am a member of this profession, and that is an "open

shop." The Leaders of Equity claimed during the strike that they did not

want a "Closed Shop" and when this statement was made, I went before

the P.M.A. and fought for and brought forward a new form of contract (the

form of contract you are using today) with far more concessions than the

Equity was demanding. I got you an extra one eighth in Chicago and other

cities where Sunday night shows had already been established. I got you

the "play or pay" clause Holy week and week before Xmas. These were

things outside of the Equity demands that I ferociously fought for, and got

for you along with everything else you wanted, and were asking for.

This contract was presented to all members of the acting profession, and

still with a far better contract than the Equity claimed they were "striking

for." The Equity crowd refused to accept peace, why? There is but one

answer, they wanted "closed shop." That was the real issue, but the

rank and file could be fooled no longer, and it looked for a time as though

the Equity Association would cave in or break into factions.

Then, Augustus Thomas was called in and brought them to their senses

and arranged a meeting that saved the day and saved the Equity. And

now perhaps you'd like to know just who called in Augustus Thomas

at the crucial moment - I called him in, and so I claim that I got for you

every advantage the new contract gives you. I claim I got you a far more

liberal and better contract than has ever been issued before. I claim

that whatever you made, you made through me and my efforts to protect

the actor while I was being condemned by the same people I was actually

fighting for.

The main issue was the "Closed Shop." That's what Equity wanted. When

I say Equity, I mean the self chosen leaders. There was just one thing I

fought for and that was "open shop" and I won. I'm for the actor. Always

have been for the actor - always will be for the actor, and any actor who

knows me knows I speak the truth. Don't let them trick you into accepting

something you do not want. Don't let them sneak this issue through under

a different name. "Equity Shop" is a "Closed Shop." And "Closed Shop" so

far as the acting profession is concerned can never be. It is a business of

unique and individual service and unless it remains so there can be no hope

for any artistic, or financial success, or achievement in the Theater of America.

That's the way I feel about it, and that's why I've fought and will continue to

fight for the "open shop." Don't let them trick you. Play the game and play it

square. Don't fight a selfish fight, fight for the Theater and protect the actors.

George M. Cohan

Don't let the council of the Equity tell you that they got you these things

because they never even dreamed such a contract could ever be had.

I got this contract for you and I got it after a long, hard, bitter fight. Ask any

member to the P.M.A. if this is not the truth.